Framing Statement

A Lost Life Found was performed in Lincoln Drill Hall, 8th May 2015. The performance was a memorial performance in memory of seventeen year old Rosamond who died in the Drill Hall April 6th 1899. Inspired by ideas and work of Mike Pearson, Michael Landy and others, I had created a performance to commemorate and remember a young, innocent girl. A Lost Life Found was a heavily influenced piece, through research and meetings with specialists and distant family members of Rosamond. The research extended as far as her hometown Chobham in Surrey.

The performance was taken place in the Phil Cosker room as I believed it represented a 1800’s gymnastic room best. The site production lasted three hours as a durational piece. For the first hour I spent it setting out the timeline that represented Rosamond’s life, the second hour was a chance to reflect and respect and the third was to pack it all away again, with the same consideration shown in the first two hours. The audience were able to walk in and out of the performance whenever they wanted, admiring the installation or eleven minute video that was on repeat, showing my journey in finding information on Rosamond. The involvement for the audience was to listen and remember. The aim was for Rosamond to be remembered as she had been forgotten for such a long time, even though her family and friends went through great lengths to make sure that didn’t happen. The memorial aspect of the performance was highly influenced by the information of her passing and Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red at the Tower of London (Historic Royal Palaces, 2014).

Furthermore, the piece A Lost Life Found depended on the symbolism and metaphor element, through representation of Rosamond’s life. Especially the rope, as the seventeen knots represented seventeen years of Rosamond on this earth.

Analysis of Process

The piece of history from the Drill Hall that took my interest through the help of the archives, was a girl called Rosamond Acworth. Rosamond Acworth was born in 1881, second child and only daughter of the Vicar of Chobham, H S Acworth and his wife Rose Acworth. Rosamond boarded at Lincoln’s Christ’s Hospital Girls’ High School, situated in Lincoln. Even though she was not with the school for long, she was considered highly by her peers and teachers. She was regarded by her teachers as ‘a little faster, and do rather more back work sometimes’. Among many other tributes, she was described as ‘…full of spirit and breezy originality’ (Lincoln Cathedral, 2012). She was the Schools Hockey team Captain, as well as having interests in gymnastics. Another passion of hers was books, which is why she joined the school librarian team and the magazine committee. Seeing as she was only at Lincoln’s Christ High School for a short amount of time, it was humbling to see how much she had achieved.

On 6th April 1899, Rosamond attended her gymnastic class as usual at the Drill Hall. As she was climbing the rope, she suddenly let herself slip, becoming unconscious when landing on the floor. Only making it 3 yards up the rope, which was strange for her usual performance, there was immediate alarm. A doctor was called and she was given resuscitation for an hour to then be pronounced dead. The school, locals of Lincoln and the locals from her home town were devastated, as the town of Chobham were all said to be in mourning for the young girl.

The dedications made in her honour in Lincoln consisted of a book case, from her cousin Lilly, given to the school. Also, a prayer desk was made in memory of Rosamond for the school, engraved with the schools sign of lilies. Lincoln Cathedral also dedicated a window to Rosamond in her honour, engraved with:

‘To the Glory of God and in loving memory of Rosamond, only daughter of HS Acworth, vicar of Chobham. She died in Lincoln Gymnasium April 6th 1899 aged 17.’ (Lincoln Cathedral, 2012)

My interest in the rope and time limit of an hour influenced my following ideas through the next couple months. I wanted to include her interests of books, sports and religion, which I believed she held close to her heart. My intentions for the show were to recognise and celebrate her fulfilled seventeen years, instead of dwelling on the years that could have been.

(Walking Artists Network, 2012)

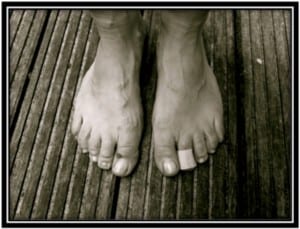

In my research, looking for inspiration to help guide my performance, I came across Amelie Daems’s Feet. What caught my attention of Amelie Daems’s Feet was the journey to rediscover past journeys and footprints of past travellers. The attempt to rekindle the history of the land from the broken bark of a tree to the fallen autumn leaves. The feet were the artwork as it showed the lining of these travels, ‘tracks to catch up on the journey just made’ (Walking Artists Network, 2012). It stated that the foot creates ‘temporary fossils pressed into sole-flesh’ (Walking Artists Network, 2012) thereby ‘the land-printed and printing foot: printed on land in the form of the path and by it, in blade marks’ (Walking Artists Network, 2012).

This reminded me of Rosamond Acworth’s journeys from walking around school, to travelling to church or the Drill Hall to attend outside school activities. I wanted to explore what routes she would have taken, especially on the last days of her life. A school teacher of hers stated that she ‘just ended her life in the full swing of her interests and enjoyment in the straightforward day’s work’ (Lincoln Christ’s Hospital School, 2011). Rosamond depended on structure and plan; therefore she must have had a planned route which she took to these places.

Through some form of documenting, whether through picture, filming or drawing, I wanted to explore Amelie Daems’s Feet’s performance, but not investigating a large scale, like the woods, but singling down the research to one journey and person, Rosamond Acworth. I believed the best way to understand her was to go to the heart of her home at Lincoln, which was her old boarding school, Lincoln Christ Hospital School and try to repeat the footsteps that she once took so that I too would have ‘tracks to catch up on the journey just made’ (Walking Artists Network, 2012).

This idea I took and visited her old school, meeting researcher Peter Harrod, who was able to give me access to an old magazine report on Rosamond’s death. Also, with Amelie Daems’s Feet in mind, I took pictures and videos of the prayer desk and bookcase dedicated to Rosamond, which is still at the now boys and girls school. I also visited Lincoln Cathedral to see the window that sparked my interest for this story at the beginning.

The magnitude of Rosamond’s window in Lincoln Cathedral and the positioning to me, struck me as important and special. Of course having anything dedicated to anyone in Lincoln Cathedral is humbling enough, but Rosamond’s window struck me as important and grand. This made me feel that the dedication must have been a high commendation for the time and the fact that she was so young to receive such an honour lead me to believe that her station in society must have been recognisable.

Michael Landy, who created the performance Breakdown, commented in an interview how dependent we are as a society on our material belongings an implied that this was unnecessary (The EYE, 2008). I personally disagreed. The objects and memorabilia’s were a part of someone’s past and the making of their future. Monuments and dedications such as Rosamond’s window proved that even though there may not be recognition from on lookers of the meaning, they could still appreciate the beauty of the memory. Rosamond’s window reflected a large part of her life, which was her belief in the church. The window would have acted as a comfort to those who knew her and missed her.

I documented the window through film and pictures which I used in my performance. I believed it reflected the magnitude and affect her death caused to the city and her home town, which needed to be highlighted to respect her memory. Tom Küpper, the stain glass specialist of Lincoln Cathedral, informed me that Rosamond gained this honour due to her father being a vicar. Also, through Peter Harrod I learnt that her father’s friend was a priest at the Cathedral. This was probably another influence for Rosamond’s commendation.

Another project that took my notice was Karen designed by Blast Theory. The idea of Karen interested me greatly as she was supposed to be an intellectual, information source life coach who was ‘happy to help you work through a few things in your life’ (Blast Theory, 2015). Karen was a specifically designed app that got to know you so it could adjust to your needs. Some information that she shared with you about yourself may have been a surprise, but it was probably given unintentionally or subconsciously when being asked questions by Karen. The performance was designed to highlight how easy it was for normal use of media e.g. Facebook or Twitter, could use information, even if you did not willingly give it. It was a site-generic performance to you phone, so your phone became the space and performance. Blast Theory stated that they ‘wanted you to be challenged about how honest and open you might be and to experience the thrill of having your personality appraised’ (Blast Theory, 2015). Karen is supposed to take in everything you say so you got a unique experience.

Mike Pearson commented, whilst speaking about his work From Memory, that ‘gossip can include extraordinarily different orders of verbal material and information – opinion, anecdote and so on, without break (so that you can move from one topic to another, without stopping)’ (Cousin, 1994, 38). Karen had the potential to be the gossiper Pearson talked about, as she gathered information and unintentional opinions the spectator had so she was capable of carrying on the conversation without faltering. Karen was described as ‘fun and funny, always cheekily pushing her friendliness into new areas. You can decide how open to be and how to handle her inquisitive nature.’ (Blast Theory, 2015) This made participants aware of how easy it was to give away information and more so, how simple it would be for someone to put pieces of their personality and traits together.

Karen inspired my performance, in the sense of telling Rosamond’s story directly to the audience. Experiencing Karen first hand, I realised how intimate and personal it felt to have the app speak directly to me as if she was a friend. It made me more willing to spend my time getting to know her and vice versa. I wanted to create Rosamond in the best representation possible through the research I gathered from the church, school and hometown of Chobham, with the intention of creating a memorial performance, giving justice to Rosamond. With the influence of Karen, I wanted to make Rosamond’s story touching and personal for the viewer to watch, so they would be more willing to watch and listen.

On 6th April 2015, I got the chance to visit Rosamond Acworth’s hometown Chobham. This date was particularly important as 116 years prior would have been the last day of Rosamond’s life. My first visit was to St Lawrence’s, the church where her father would have preached. The three windows her brothers William, Cecil and Bernard dedicated to her were heart-warming. They were positioned in a prominent place where by day it was lit perfectly by the bright sunshine. Three bible passages were named under each widow scene, my favourite being Jairus’ Daughter. The chandelier Rosamond’s father had named after Rosamond, was also present after 116 years. I found an engraved dedication on the chandelier for Rosamond followed by, ‘he liveth long, who liveth well’. Furthermore a plaque was dedicated to her father after a side alter he created. Also the front bench for praying and preaching was dedicated to Rosamond’s brother William, after his death.

I followed the road to the graveyard dating as far back as the 1800’s. As I filmed the walk, it reminded me of An Exeter Mis-Guide performance by the company Wrights and Site. As commented by Mike Pearson, Wright and Site ‘walks offer specific routes’ (Pearson, 2010, 25) whereby your journeys could be simply led by a dog. The experience ‘suggest[ed] a series of walks and points of observation and contemplation within the city of Exeter’ (Wrights and Sites, 2008). Similar to my own performance, Rosamond was taking me on a journey of her life.

The visit overall was very beneficial. I was able to walk in the footsteps of not only Rosamond when she was 17, but Rosamond throughout her whole life, growing up in Chobham. Furthermore, I was able to walk in the footsteps of her family on the day of the funeral, what they would have seen, heard and felt. It made my view of her grow stronger in my journey to finding her and certain that I had gained the information I needed.

In the final stages of A Lost Life Found my thoughts led me to the Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red at the Tower of London. This site specific display was a commemoration to the soldiers of world war one. ‘The poppies encircled the iconic landmark, creating not only a spectacular display visible from all around the Tower but also a location for personal reflection’ (Historic Royal Palaces, 2014). I believed it was the first time the war was put in real respect to the mass of the situation and how much it devastated and effected lives.

This reminded me of my own performance due to the memorial aspect of the performance. The impression and remembrance that it gave to any onlooker was the outcome I wanted for my own work. The care and attention given to each poppy was the focus I had given Rosamond and what I wanted to do in the performance. I had researched every possible detail so, as the creators of Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red had achieved, I wanted to take care to represent and nurture every fine detail of Rosamond in respect.

Evaluation of the Performance

The final performance was a durational piece lasting three hours long. At the start of the first hour, I walked into the Drill Hall, carrying the rope, which my performance was going to resemble a large portion of my performance. The first hour was to place the timeline (or rope) across the floor. Objects, representing parts of Rosamond’s life were placed at certain points on the timeline, depending on the part of the rope. I placed wedding ribbon and confetti in Rosamond’s first years representing the years her father and mother were happily married, before her mother was referred to a hospital for, supposedly, postnatal depression. Other elements were placed, such as a bible, for her faith, books, for her love of reading and spoons with blue or pink ribbon on to represent her brothers and Rosamond. At the end of the rope were hockey sticks, lilies and picture of Rosamond’s thought to be school friends, in representation of her school. Throughout the rope timeline, I placed roses; this was in memory of her mother, Rose Acworth. I believed that throughout her life, Rosamond’s mother would have been close to her heart and life.

For the second hour, after I had placed the items on the rope, I knelt by the window in the Phil Cosker room and prayed in silent respect for Rosamond. Every time there was an appropriate silence, I said ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Rosamond. Only daughter of H. S. Acworth, vicar of Chobham. She died in Lincoln gymnasium April 6th 1899, aged 17. God grant that we, who knew and loved her here, may meet her again in the home beyond.’ This passage was quoted from the window in Lincoln Cathedral and the prayer her school published, dedicated to her, after Rosamond’s death.

The last hour, I packed everything away, reversing what I had done in the first hour. After everything was collected and in its original place situated at the back of the room, I carried the rope back out of the Drill Hall, as if she was passing on. Throughout the performance, a simple video of 11 minutes played on repeat, on my journey of finding Rosamond. The video showed journeys and dedications I found when trying to find out more information on Rosamond. The reasoning for the distinction between certain actions in each hour was to show respect to the doctor who tried to save Rosamond’s life for an hour. I couldn’t let that crucial and touching part of the history pass without some recognition.

The audience were allowed to enter and exit whenever, meaning they could see the effects of the durational performance when they wanted, seeing the changes. In hindsight, I should have placed a notice on the door or wall, explaining the piece, because when the audience entered half way through the video, it wasn’t clear as to what I was doing. Furthermore, the notes and pegs I left on the timeline, could have been bigger to make the performance clearer for those who did not look close enough at the details on the rope. The venue was a different and challenging environment, but at the same time became more sentimental. I felt more emotionally invested in this piece of drama because I was the first to do it and it was for a real person. The dedications and passages I found for Rosamond meant something to me in the end, because the effort and love that went into preserving Rosamond’s memory by her family and friends were touching and humbling. The whole experience is something I will be proud of and will remember.

Words: 3,005

Bibliography

Lincoln Cathedral (2012) A Memorial to Rosamond Acworth 1881-1899 [online] Lincoln Cathedral. Available from http://lincolncathedral.com/2012/04/a-memorial-to-rosamond-acworth-1881-1899/ [Accessed 20 February 2015]

The EYE (2008) Michael Landy – Break Down. [online] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hYUnkW4sNA (Accessed 1 February 2015)

Walking Artists Network (2012) Amelie Daems’s feet, Conan Lawrence. [Online] York: Available from https://walkietalkietoo.wordpress.com/2012/09/18/bare-feet-conan-lawrence/ [Accessed 1 March 2015]

Lincoln Christ’s Hospital School (2011) Occasional Paper No 1: A Memorial to Rosamond Acworth. [Online] Lincoln: Available from http://www.christs-hospital.lincs.sch.uk/joomla15/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=732:a-memorial-to-rosamond-acworth&catid=55:lchs-archive&Itemid=250 [Accessed 24 February 2015]

Blast Theory (2015) Karen. [online] Brighton: Blast Theory. Available from http://www.blasttheory.co.uk/projects/karen/ [Accessed 4 March 2015]

Cousin, G. (1994) An Interview with Mike Pearson of Brith Gof. Contemporary Theatre Review, 2(2) 38.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wrights and Sites (2008) An Exeter Mis-Guide. [online] Exeter. Available from http://www.mis-guide.com/ws/archive/exetermg.html [Accessed 4 April 2015]