Framing Statement

We Need You and Your Footprints was a site specific performance/installation developed and performed at the Lincoln Drill Hall on Free School Lane in Lincoln on Friday 8th May 2015. This piece was an installation that developed into a performance within the three hours the audience were there, with each performance lasting for 16 minutes and 40 seconds, and was performed twice.

As part of our pre-performance we set up a printing/recruitment desk in the corridor to the auditorium and leading to this was a poem that read “Walk with us and listen clear, the footprints of our soldiers are lying here” (Baillie et al, 2015) written on some footprints. Members of the public entered the corridor which was fashioned to look like the WWI recruitment process, as Laura was sat making prints and surrounded by posters. They were asked to make a boot print which they could sign with their name and were instructed by myself and China to place within our installation situated around the corner from the corridor. After replacing an already installed print with their own, they posted the old boot print into a black post box. They were then free to move on to other performances and return to see our performances, at 2:30pm or 4:30pm, if they wished.

The installation was made in front of the auditorium seats, which had been pushed back, with a cyclorama stood before them. We outlined the area with masking tape and over an hour or so filled it with approximately 500 boot prints in a grid formation, which after two performances would equate to 1000. This was to signify the number of men in a battalion, along with the 16 minutes and 40 seconds duration which equates to 1000 seconds, as our piece focused on the 4th battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment, who trained within the space of the auditorium during the First World War. We set the prints out in a grid formation to replicate the stringent tasks the soldier’s performed, and we then added our own ephemeral prints by performing bare-foot and standing between the prints as we moved.

As our performance began, projected onto the cyclorama was a time-lapse video of the Drill Hall’s auditorium during the replacement of the old rig for the new one by the technical team, called “Stop Motion Rig” (Lincoln Drill Hall, 2012). This juxtaposed with our boot prints as we aimed to bring back the past to the present when the public meshed their prints with the soldier’s prints. These binaries of past/present and old/new were intertwined throughout our piece and became our theme. An audio clip of “left, right” played for the duration of our performance along with a countdown from 16:40 featured in the corner of the video. The repetitive sound timed with our steps mimicking the soldier’s drills as the three of us walked up and down 8 rows each, scrunching the foot prints and then going back on ourselves to lay them flat again.

Analysis of Process

During our first session at the Drill Hall we explored all areas of the site by using Willi Dorner’s Bodies in Urban Spaces as a stimulus. The idea that “passers by, residents and audience are motivated and prompted to reflect their urban surrounding” (ciewdorner) made us notice particular places we may otherwise not have paid any attention to. By creating shapes in the entrance to the Drill Hall, we morphed this idea into a drill sequence in which the rest of the class recreated our shapes. This then developed, the next week, into exercises influenced by the shapes, which we instructed the class to perform in a drill situation as we shouted commands and issued pardons to the people who completed the activity. Doing this exercise informed our choice in which period of the Drill Hall’s history we would chose to research, as we began studying the 4th battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment during WWI. As Brueggemann states, “Place is space in which vows have been exchanged, promises have been made and demands have been issued” (1989, 26 in Pearson, 2010, 108). We were intrigued by the concept of not necessarily acting as drill leaders but by putting an audience through tasks similar to that of a drill so they could experience what the soldiers endured themselves. However, after some deliberation we decided not to put the audience through drill exercises as we had to consider the physical fitness of members of the public and so we inverted the idea to instead have us perform the drills.

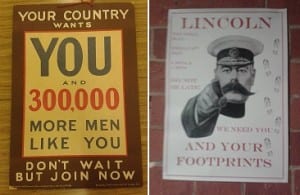

Soon after our decision to explore the Drill Hall’s WWI history, we were able to visit the Lincoln Archives, where we found some interesting information about that particular period. We discovered that the 4th battalion, who were volunteers who trained regularly during the decades leading up to the First World War, took part in drill competitions every year. Unfortunately, there were no concrete examples of what activities they took part in and so we could not use these facts to our advantage. However, we also came across some WWI recruitment posters which consequently influenced our whole pre-performance, as we wanted to recreate how soldiers would enrol into the army before beginning their training. This resulted in us setting up a desk surrounded by posters featuring the title of our performance and Lord Kitchener, a famous military leader from WWI. “Performance recontextualises such sites: it is the latest occupation of a location at which other occupations – their architectures, material traces and histories – are still apparent and cognitively active” (Pearson, 2007c in Pearson, 2010, 35), with the latest occupation being the stage and the WWI history being what we wanted to extract. Bringing out the past into the present and juxtaposing them with each other then became one of our main themes and was a concept we constantly tried to stay loyal to.

Eventually, we agreed on the idea of laying out footprints to symbolise the drills rather than re-enact them as Laura was interested in creating a visual image with paint and I was intrigued by the action of polishing a boot. These two ideas came together when we decided to use boot polish to make the boot prints as the polish would also play with the audience’s olfactory senses if they could smell it as we made the prints throughout the performance day. China, Laura and I continued to experiment with several different ideas on how we could envelop more of the audience’s senses throughout our piece. At the beginning of the rehearsal process we had Laura read out poetry while I laid out footprints, however this seemed too melancholic as the aim of our piece was to reflect the drills that took place and not commemorate the soldiers’ deaths. This triggered us to find audio clips of drill commands but we could not find any from the early 20th century and so we had to set aside this idea. In the end we chose to write our own short poems and use them as instructions, almost, to direct the audience around our space. We had the first poem in the entrance to the corridor to tell the public what was happening in the auditorium. The second poem led from the corridor into the auditorium and read, “You may wish to leave, but feel free to stay. Our piece will progress so return through the day” (Baillie et al, 2015) which was used as an invitation for the audience to pass through our performance space as they pleased.

We decided to use the auditorium for our performance as this was where the drills would have taken place and as we were using a big space we wished to fill it with prints, bringing back all the past steps the soldier’s would have made. Because of this decision we were advised to look at Stan’s Cafe’s Of All The People In All The World as they worked with large quantities of rice and made installations to visually show statistics from the places they toured to. “Of All The People In All The World uses grains of rice to bring formally abstract statistics to startling and powerful life” (Stan’s Cafe, 2014) and so the scale of these installations influenced us to consider the rather improbable idea of laying out 300,000 boot prints, which we took from the number on the recruitment poster, and creating an installation as well as performing.

As we already had a pre-performance (the recruitment desk) and the performance would involve us laying out a significant amount of prints, we wanted to make a post-performance too so as to add to the overall experience. The images of the Fleur de Lis dotted around on the Drill Hall walls had previously been pointed out by another class member. This led me to suggest we create an image of the Fleur de Lis with the footprints after they were all laid out and leave it as an installation for our post-performance. This would solidify the connection of our piece to the Lincoln Drill Hall as the Fleur de Lis features not only on the girders in the auditorium where we would perform but also on the Lincoln coat of arms. We also debated creating the map of Lincolnshire as an image but felt this would not relate to the Drill Hall specifically and would not be as recognisable an image as the Fleur de Lis. Eventually, we felt that creating an image would not actually fit with our theme of past and present and decided against this idea.

The idea of laying out 300,000 footprints became redundant when we realised we would struggle to simply fit 3,000 prints in the auditorium as we placed them in a grid formation instead of side by side. Simply laying out prints also seemed quite monotonous to us and so we thought about scrunching the prints up into balls once they had been laid out to symbolise the straight-laced and newly trained recruits transforming as they dealt with the horrors of war. Developing on this, we would subsequently flatten the prints which would still remain creased, to represent the soldiers returning home but still affected from their time away.

During research on the 4th battalion, I came across a statistic which would become a significant part of our final idea – “Battalion: 1000 men commanded by Lt Colonel” (Lincolnshire County Council, 2014). From this I suggested we only use 1000 boot prints and give ourselves a time limit of 1000 seconds. But, as there were only three of us and we had to scrunch and flatten the prints in that time as well, we concluded that we would do two performances with 500 prints instead. I also suggested that we use an audio track that repeated “left, right” for every second that passed so that we could lay down the print in conjunction with the track. This would make clear that our piece focussed on drills and would potentially keep the three of us in time as it did for soldiers. Along with the audio clip, we wanted to project a countdown onto one of the walls as a visual aid for audience members and to emphasise the time constraint.

Here is a 1 minute clip of our audio track:

In one lesson we were shown the “Stop Motion Rig” time-lapse video of the Drill Hall’s technical team taking down an old rig and replacing it with a new one. We then thought about how having that video projected along with a countdown during our performance would strengthen our past and present theme, as we would be displaying the current use for the Drill Hall, while we performed its past use below the projection. Developing on this idea and solving our problem of creating a post-performance, we decided we wanted to film our performance and create our own time-lapse to leave as a document of our present in performance, which would become our own past once performed.

The final company we were influenced by was Lone Twin and their performance Totem which saw them carry a telegraph pole through Colchester town as the crow flies, taking them through buildings and shopping centres. This was commissioned after a tornado struck East Anglia and represented the reparations to the town. Totem influenced our piece through its use of audience participation as the two performers, Gary Winters and Gregg Whelan, “invite[d] people to give us their attention. At times, they [were] invited to do something with us” (Lavery and Williams, 2011, 9). They asked passers-by to help them carry the pole and contribute their stories or pictures and then carve their name into the pole. We altered this idea to fit our piece by asking the public to sign a print they made and then place it amongst the rest as we laid them out, as we decided that we would no longer lay the prints within the 16 minutes 40 seconds, only scrunch and flatten them. For us, this meant that “the demands upon [the audience] to contribute material [were] substantial” (Pearson, 2010, 177-178), as the public would be placing their prints with the ones we were laying for the soldiers and thereby also maintaining our past/present binary.

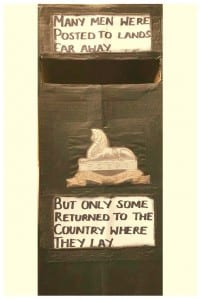

Another decision we made was what the public would do with the footprint they took after they had placed their own. I made the suggestion that they could somehow be posted to Egypt as the 4th battalion were during WWI. China developed this idea by proposing we make a black box to connect our piece with the fact the votes had been counted in the auditorium the night before our performance day. This was another past/present link as we juxtaposed the soldiers leaving for war with the election, which is essentially a political war between parties. And our final poem featured on the black post box, which sat just past the poem in the doorway, explained what the post box symbolised – “Many men were posted to lands far away, but only some returned to the country where they lay” (Baillie et al, 2015). Along with this poem was an image of the Lincolnshire Regiment’s symbol, the sphinx, which is featured on the memorial plaque in the Drill Hall’s café and so secured another link in our piece to the 4th battalion.

Performance Evaluation

One of the most important aspects of our performance was the timing. We wanted to strictly fill all of the 16 minutes and 40 seconds with action as its significance, along with the amount of footprints, was the frame of our final piece – 1000 seconds, 1000 footprints and 1000 soldiers. Unfortunately, as we had limited access to the space towards the end of the rehearsal period, we were not able to practice filling the time limit, which resulted in us finishing our performance around 1 minute too early. We also began the performance in step together while scrunching, but lost our synchronisation once we started flattening the prints. However, I liked that we fell out of time with each other during the second part of the performance as it reflected the drills and how some soldiers would not be as physically capable as others.

As it was a durational performance, I did find it physically gruelling and experienced loss of breath, but the few audience members who did stay for the full performance commended us for our persistence. It was unfortunate that we only had a few people watch both of our performances, but we expected this and had offered them the option to observe. Alternatively, most people who passed through our space did wish to leave a print and for me, this was more important than our piece being watched, as our aim was to juxtapose the past with the present through soldiers and the public’s prints.

Overall, I do think our performance worked well as a whole, with the audio and video coming together with the task we were performing to create a hypnotic piece. But I do think we could have expanded on our pre-performance more, by adding other tasks for the audience to participate in and contribute to the complete image. If we were to install and perform our piece again, I would suggest we make an instruction leaflet for audience members to take so they would know how to interact with our piece. This would enable China and I to lay out prints at a slower pace and create the image of the filled space more gradually, as well as give the audience chance to appreciate the image and its significance. Also, I would have us perfect our timing, so as to fill our countdown to as close as we could, by either adding in an extra task for us to complete, or taking more time on the two tasks we did have. I feel we could have related our piece more specifically to the Lincoln Drill Hall by finding the soldier’s names from the 4th battalion and writing them on the corners of the prints, as we asked the public to do.

The research I have undergone and the process for our piece has opened my eyes to an unusual and contemporary style of performance, one of which insists on leaving all preconceptions of theatre behind as you are taken from that space into another. I now have an appreciation for how site specific work “offers spectators new perspectives upon a particular site” (Govan et al, 2007, 121) and how even a theatrical space can be transformed into something completely different.

And here is our post performance…

Word Count: 2,930

Work Cited

Baillie, L., Boughen, L. and Pacey, C. (2015) We Need You and Your Footprints. [performance] Lincoln: Lincoln Drill Hall, 8th May.

Cie Willi Dorner. Available from: http://www.ciewdorner.at/index.php?page=start [Accessed on 12/2/15].

Govan, E., Nicholson, H. and Normington, K. (2007) Making a Performance: Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices. Oxon: Routledge.

Lavery, C. and Williams, D. (2011) Practising Participation: A Conversation with Lone Twin. Performance Research, 16 (4) 7-14.

Lincolnshire County Council (2014) Royal Lincolnshire Regiment During World War I. [online] Lincoln: Lincolnshire County Council. Available from: http://www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/residents/archives/collections/guides-to-sources/royal-lincolnshire-regiment-during-world-war-i/118960.article [Accessed 8 March 2015].

Mike Hurley (2012) Stop Motion Rig [online video] Available from http://www.lincolndrillhall.com/about-us/the-venue-its-history [Accessed 13 May 2015].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stan’s Cafe (2014) Of All The People In All The World [online] Available from: http://www.stanscafe.co.uk/project-of-all-the-people.html [Accessed 14 May 2015].